Rektusscheidenhämatom

Rectus sheath hematomas, as the term implies, occur when a hematoma forms in the rectus abdominis muscle/rectus sheath. It is most common in its lower segment and is generally self-limiting.

Epidemiology

Rectus sheath hematomas are more common in women with a 3:1 F:M ratio.

Clinical presentation

Rectus sheath hematomas most often present as acute onset of abdominal pain with a palpable abdominal mass. Additional findings may include fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, and abdominal guarding. Depending upon the size and location of the hematoma, patients may also present with signs of hypovolemic shock or even abdominal compartment syndrome .

Pathology

Etiology

The majority of hematomas result from the rupture of epigastric vessels or by tearing of the fibers of the rectus abdominis muscle. This can be due to :

- spontaneously in the context of anticoagulation therapy (most common)

- direct or indirect trauma

- coagulopathies e.g. cirrhosis

- degenerative vascular diseases

- iatrogenic, e.g. from high femoral arterial puncture

Radiographic features

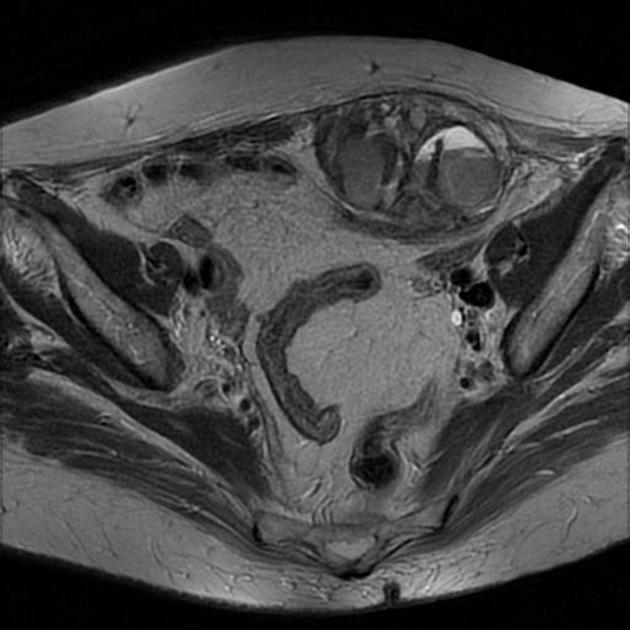

Rectus sheath hematomas are classified based upon computed tomography scan findings to guide treatment .

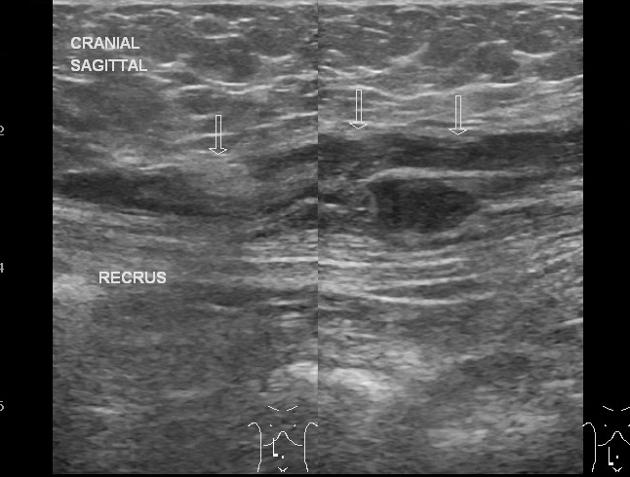

Ultrasound

- heterogeneity in rectus abdominis muscle

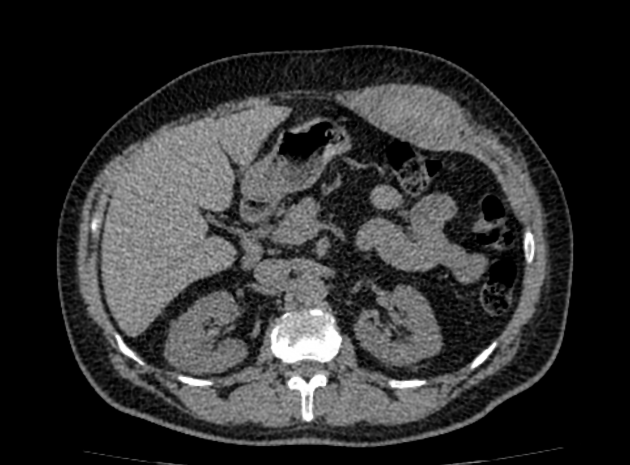

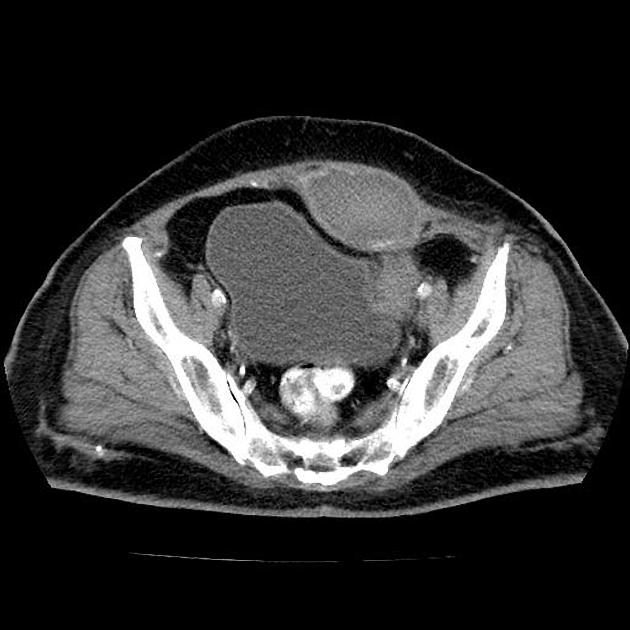

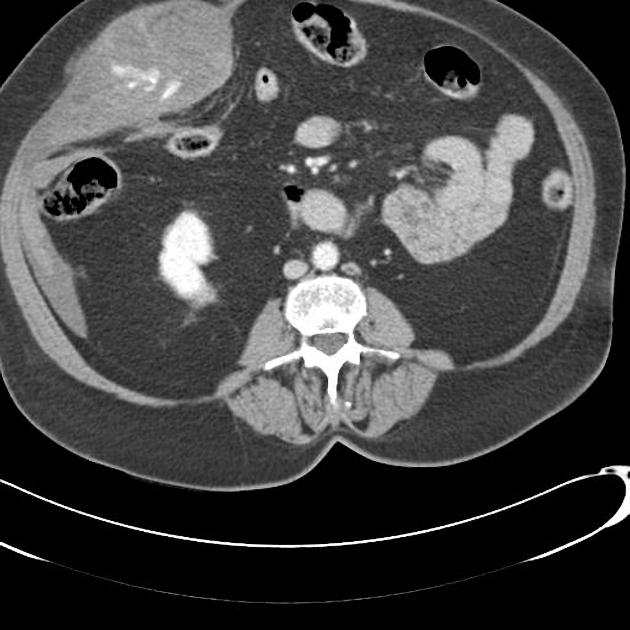

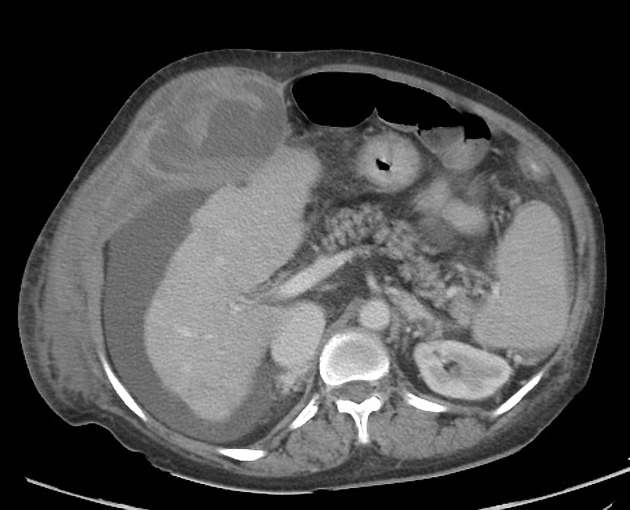

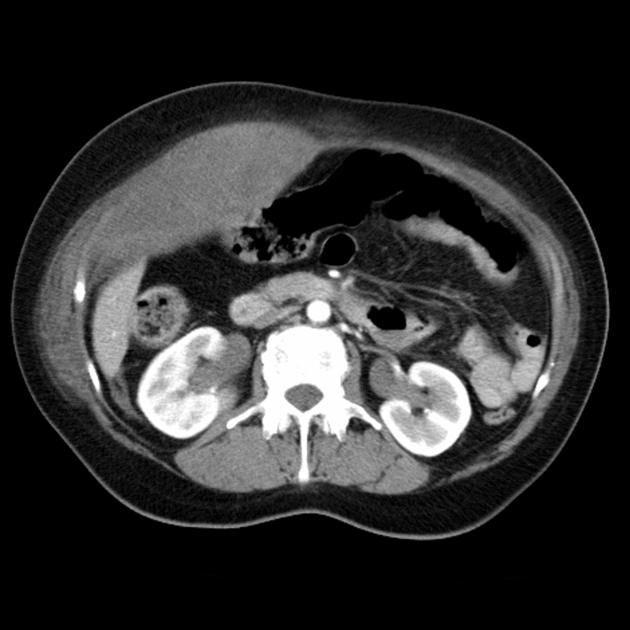

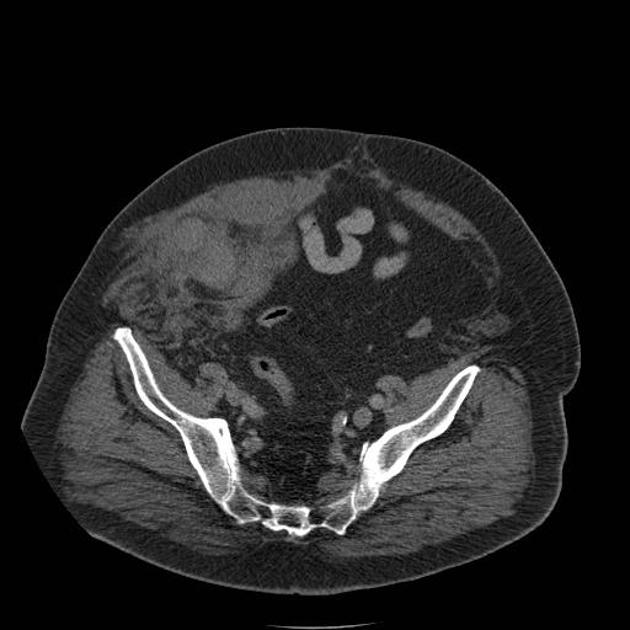

CT

- hematoma is confined to the abdominal wall.

- high attenuation on unenhanced images

- lack of enhancement

- resolution on follow-up studies helps confirm the diagnosis

CT classification

- type I: small and confined within the rectus muscle; does not cross the midline or dissect fascial planes

- type II: also confined within the rectus muscle but can dissect along the transversalis fascial plane or cross the midline

- type III: large, usually below the arcuate line, and often presents with evidence of hemoperitoneum and/or blood within the prevesical space of Retzius (retropubic space)

Treatment and prognosis

Management of rectus sheath hematoma is determined by the patient's clinical status, the underlying cause, and the classification.

- type I:

- almost all of these patients are haemodynamically-stable without any change in serial hemoglobin or hematocrit levels

- patients are treated conservatively with bed rest, analgesia, compression of the hematoma, and reversal of anticoagulation when appropriate

- hospitalization is not usually required for affected patients

- types II and III:

- patients can present as haemodynamically-stable or show signs of hemodynamic compromise (e.g. altered mental status, hypotension, tachycardia, acute kidney injury, etc.) with an abrupt or gradual decrease in hemoglobin or hematocrit

- patients in hypovolemic shock should be resuscitated aggressively and promptly referred for either angiography with embolization (first-line intervention at facilities that have interventional radiology capabilities) or surgical ligation of the bleeding source

Siehe auch:

- Desmoid-Tumor der Bauchwand

- Bauchwandlipom

- Musculus rectus abdominis

- spontane Einblutung

- Embolisation Arteria epigastrica inferior

- pseudoaneurysm of the inferior epigastric artery

- Bauchwandhämatom

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Rektusscheidenhämatom:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Rektusscheidenhämatom: